The Lively Lad is six years old now, and he stands as tall as my sternum. In another six years he may very well be looking me in the eye without my picking him up. For many dads, that would be a source of pride, but for those of us who are fathers of black boys, it is also a cause of some anxiety. Right now, he still falls in the “cute kid” category, but I know that will not last a whole lot longer.

In the wake of the deaths of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner and Michael Brown, it became impossible for many of us Americans who consider ourselves White to ignore the disproportionate use of officially sanctioned force against Black Americans – particularly young Black men. For those of us who are White parents of transracially adopted Black boys, the sense of vulnerability is hard to reconcile with our own experiences.

Thankfully, we have Ta-Nehisi Coates to help us along with his very moving Between the World and Me. He would probably be the first to point out that he is one Black voice among many, but the very personal tone of this open letter to his fifteen-year old son makes it especially poignant. For me, it provides an extremely thoughtful and perceptive first person account of being a Black man in America, something I will never be able to provide for the Lively Lad.

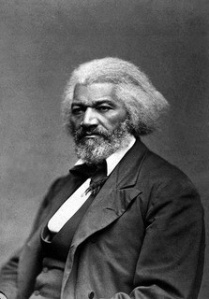

Coates’ path to becoming a successful writer for The Atlantic was not a typical one by any means. He is the son of Black intellectuals, but he acknowledges that many of his important life lessons came on the violent streets of West Baltimore. His descriptions of his early experiences and awakening at Howard University point out what a unique institution and refuge it is for Black Americans. I particularly appreciated how he portrayed the philosophical struggle within the Black community itself between engaging with the White paradigm and separatism – and long history of debate from Frederick Douglass to Marcus Garvey. But Coates is most definitely a 21st-century Black voice, certainly an heir of James Baldwin, but definitely addressing what it means to be Black in this day and age.

One point that emerges from the book is how Black American children (as well as kids of other marginalized groups that don’t fit the dominant model) inherently are taught to “code switch” as a survival mechanism. While it is technically a linguistic term, it essentially means that you need to know where you are and what is expected of you at all times, and adjust your behavior and speech accordingly. This is a key reason that there has been so much historical resistance to transracial adoption from parts of the Black community – if Black children are raised by parents who have never had to code switch in their lives, are those children being denied an essential survival skill? We all adjust our behavior to the circumstance – there are candid conversations I have with old theater friends that I would probably never have in my job environment – but the stakes are higher if you are in a circumstance where someone might regard you as a threat. Coates recounts a time when he called out a perceived racial slight to his son, and then found himself on the defensive for doing so. The outrage he felt in that situation was partially due to how he was made the bad guy for taking an aggressive comment “the wrong way,” but also anger with himself for failing to remember the right “code” for where he was.

But the overwhelming message for me was just how vulnerable Black American men can be to violence, both sanctioned and unsanctioned. Coates had a Howard acquaintance named Prince Jones who came from a middle class Black family. He lived a law abiding life, was a charismatic figure, and had a promising future until an undercover cop followed him across several jurisdictions with no solid motive to do so and shot him down near his home. Generations of caring and sweat and sacrifice and love invested in this young man, all ended by a single violent act from a law enforcement agent. Imagine living with the constant subterranean fear of losing your life for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Prince Jones’ death clearly shook Coates very deeply.

I was in the wrong place at the wrong time once in my life. In the summer of 1991, when I was part of the acting company at the Colorado Shakespeare Festival in Boulder, someone randomly attacked me at 12:30am outside my apartment complex. After passing some people arguing at the bottom of the steps to the building, I realized as I walked up Broadway under the shadow of some trees that someone was following me. Before I could turn around, I took a heavy blow to the left side of my head. Fortunately, my attacker did not continue to hit me. The next thing I remember was waking up in the hospital six hours later.

For years I have said that my guardian angel was working overtime that night, as someone anonymously called an ambulance. When the ambulance arrived, there were empty ice trays and towels at the scene, but no one was around to talk to the drivers. The left side of my face was a purple mess and my eye was swollen shut, but luckily I have a hard skull and there was no fracture. They kept me in the hospital for two days to make sure there was no major damage to my eye, and to keep an eye on the concussion I suffered. The best part of the experience may have been the headline in the Rocky Mountain News: “Shakespearean Actor Beaten on Broadway.”

It was a sobering time for the entire Shakespeare company, and Boulder is a small enough town that the incident received a fair amount of attention. Some of my colleagues came to visit in the hospital, and the uncomfortable reactions to seeing me were interesting in retrospect – forced jocularity, unabashed shock at my pulped face, studiously avoiding looking at me. They were all clearly feeling unsafe themselves. I’m grateful to them all for showing up, and eternally grateful to two of my dear friends for managing to communicate the shocking news to my parents without sending them into cardiac arrest. All of those visitors were some of my angels as well.

As I reflect on that time after reading Between the World and Me, there are two visits that stand out to me. The ethnicity of the acting company was almost all White, but there were a handful of Black actors as well, two of whom came to see me in the hospital. While I wouldn’t say they were immune to the shock of seeing me, they handled it differently. One of them was a big man with whom I crossed broadswords every night on stage, who grew up in a rough part of Chicago (if I recall correctly). I got the sense from him that he was sympathetic, but also really understood just how lucky I was that it wasn’t worse. The other was a wonderful woman who, as I recall, had grown up in an itinerant military family. She was the one who was able to look me in the face, give me a drink of water or change my ice pack, and generally provide me some real relief and comfort. For both of them, there wasn’t the same sense of shock that such a thing could happen. I can’t speak for them – but the way they took it in stride speaks volumes to me now.

This is where you might expect me to say that I have a special understanding of the vulnerability in a violent world that Black men face, as Coates describes in his book. No, I still don’t, because I am still a middle-aged white man who can go most places I want to without too much fear of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. While there may have been some PTSD for a short time after the incident, I can now say with confidence that I don’t walk in overwhelming fear for myself. And that is a manifestation of my white privilege.

But perhaps I haven’t accounted for all the angels from that night. Perhaps the person who knocked my lights out was another angel – one who was giving me the visceral experience of being a victim of violence. An angel who allowed me to feel the indifference of the police detectives who interviewed me, presuming that I had somehow provoked the attack, and who then did absolutely nothing to follow up on the incident. An angel who showed me the helplessness and fear that my parents felt when hearing about the attack. And above all, an angel who opened my eyes to how one random act of violence can irrevocably change – or end – a life well lived.

My experience was ultimately a bump in the road of my life. But I would be a fool to lose perspective and forget its lessons as the Lively Lad grows older.

© 2015 Thomas C. Elliott

Photo Attribution: maren_photography, elycefeliz